We are happy to share a guest blog post by Ana Guerra, a masters student at Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Brazil. She currently researches platform and algorithmic labor in Brazil, with an emphasis on Uber and Uber drivers’ experiences. Ana can be found on Twitter @anagvguerra. As Brazil becomes the next hotspot for the global pandemic, Uber drivers have to choose between risking their wellbeing and giving up their main source of income. In this article, Ana raises the question: what is new about this?

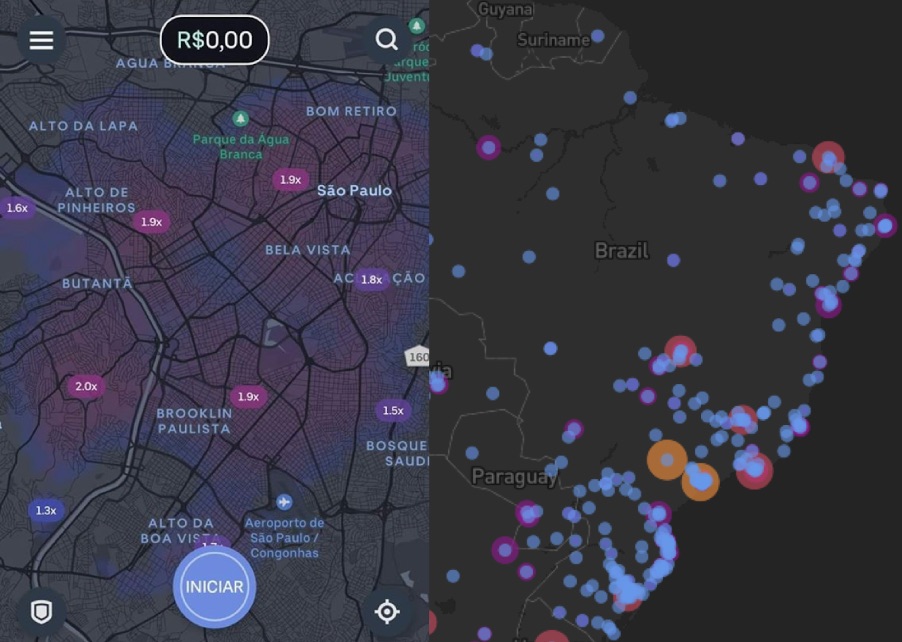

From left to right: (1) a screenshot of Uber Driver app containing the representation of surge pricing in São Paulo, the Brazilian city with the highest occurrence Covid-19, posted by a driver on a Facebook group on May 11th; (2) A Screenshot of the Covid-19 confirmed cases map produced by HealthMap.org.

Uber’s urge to mitigate uncertainties is notable in its operational and rhetorical efforts, as illustrated by the forecasting solutions aimed at predicting and managing the spatiotemporal dynamics of what is referred to as “the real world” 1. Uber employs a series of techniques to algorithmically manage drivers’ labor 2, often presented as tools to stabilize uncertainties and help drivers make more profitable decisions. This incorporation of predictive modeling to workers’ routines resonates with what Adrian Mackenzie (2015) has identified as the generalization of prediction into everyday life. Since Covid-19 started taking over our daily thoughts and affects, the “real world” seems to be getting a lot more real and our relation to prediction a little more intimate.

The new coronavirus has twisted our experience of time and space. An invisible agent, which we may or may not be carrying around inside our cells or on our clothes, rapidly unsettled the steady references around which we organized our routines. As a wide variety of data, predictive models, projections and visual representations try to render this experience a little more intelligible, the unknown keeps finding ways to confront us from unexpected angles. Any flash of certainty is found to be short lived and no amount of projections or animated graphics is able to minimize this. In a way, our computational narrative that privileges datafied and prediction-oriented ideals of truth is progressively destabilized. Yes, we keep on counting — counting patients, bodies, days — but our pace has changed.

Despite the globalized sense of uncertainty, some places feel more uncertain than others. In Brazil, signaled as Covid-19’s next hotspot, the “real world” is met with a dose of fantastic realism. Amidst underreporting, lack of testing, endless conflicts between health authorities' and President Jair Bolsonaro’s positions, news about collective graves and fake news about caskets filled with rocks, Brazilians find themselves in a rather chaotic scenario. Meanwhile death toll keeps rising as the poorest layer of the population is increasingly affected by Covid-19 and the collapsing social-economic system.

Among those caught in despair are many of Brazil's over one million Uber "partners" 3. The country is Uber’s largest market outside the U.S. Since it entered Brazil in 2014, the platform quickly positioned itself as a transportation solution for lower income and underserved communities, forging a quasi-infrastructural role. It also holds a privileged and ambiguous position as an alternative to unemployment, since many rely on Uber and similar platforms as their major source of income. Right now, however, this income is drying up and some drivers report up to a 90% decrease in rides.

Uber's responses to the pandemics do little to appease uncertainty in this case. As part of a set of "resources" directed to Brazilian drivers, the platform announced a financial assistance plan (lasting up to 14 days) to "partners" either diagnosed with Covid-19, classified as a suspicious case, or part of a risk group. Their eligibility must be confirmed by official documentation containing detailed information. Rather than offering a fixed compensation, the assistance is calculated based on driver’s average earnings for the past three months, being closely tied to their individual performance.

The policies that inform the assistance plan’s distribution also have an extremely short lifespan. The rules described above were updated on April 17th and are said to be valid only until May 8th 4. This is exacerbated by a paradoxical treatment of "risk". Once drivers request the assistance, their accounts are automatically deactivated for safety reasons. However, this does not guarantee their eligibility, putting them in a dubious position: the driver poses as a risk, and therefore is prevented from working, while simultaneously not (yet) deemed at risk — thus, no assistance is granted.

To learn more about drivers’ perspective, I interviewed three drivers — Giacomo, Antônio and Verón — from Belo Horizonte, the 6th most populous city in Brazil. I also drew on over 50 comments on a YouTube post made by Samuel, an Uber driver and YouTuber who shared my questions with his followers.

All three interviewees are still working. As they drive, SARS-COV-2 may be riding in their back seat, a risk worsened by careless riders. Giacomo estimates that out of ten passengers he picked up, two wore a mask. Antônio’s wife is diabetic, a risk group for Covid-19. He chose to continue working so they could afford her a balanced diet. He purchased hand sanitizers and even though he could request Uber's one-time BRL 20,00 refund for hygiene items, he chose not to. An "insulting help", he says, "it's offensive". They all share the sense that demand has slowed down, which may mean sitting alone in the car for a couple of hours. The job has become a little more solitary. Verón, who sees driving for Uber as a sort of therapy, notices that riders became less inclined to chat.

Most drivers who responded to Samuel's YouTube video seem to have quit driving for the time being. Fear and safety appear as the main reason for that: "I already had a sense of fear before Covid-19, let alone now" writes one user. Working or not, drivers readily felt the financial consequences of the pandemic. Some are returning their rented cars (about 160,000 of them, according to car rental companies). Others are unsure how they will pay the next installment for the vehicle they bought precisely to become Uber drivers. Many resort to the Government's emergency income 5. While a few requests were accepted and a couple declined, most drivers are met with the "under evaluation" message accompanied by an ambiguous advice to "try again tomorrow" (some have been trying again for over a month). As for Uber's assistance, the majority of drivers don't meet the requirements and exhibit a general feeling of distrust towards the platform: "Uber does nothing for us", says one driver.

Asked to describe the current moment in one word, drivers drift from "uncertainty", "fear" and "frustration", to "resilience" and "perseverance". But what does this mean? Are these feelings new? Looking at how the pandemic is affecting Uber drivers may ultimately tell us more about these drivers’ “pre-existing conditions” than about the immediate impact of the pandemic itself. The current circumstances thus invite us to defamiliarize a long naturalized state of precarity. As philosopher Judith Butler suggests, by asking about Uber drivers conditions under the pandemic, "we are also asking about the conditions of life and death that hold for the social organization of labor".

Uncertainty is no novelty. As much as they are used to being counted — working under a highly datafied labor regime, continuously being judged by their performance metrics — Uber drivers are also used to count. Trying to estimate their daily earnings while dealing with the variable fees charged by Uber after each ride, calculating their gas and maintenance spending, planning to pay for car rents or installments – these are all part of drivers' routines. They also spend time and energy coming up with strategies and goals to optimize their productivity. Life as an Uber driver is marked by a precarious drive towards short-term predictability, while the broader future remains obscure.

If we bring risk back into the equation, the conditions of life and death are made more evident. Butler asks "who risks their lives as they work? Who gets worked to death?". Getting worked to death is a common metaphor for Uber drivers. As one driver (who I interviewed in 2018, after car damage stopped him from working for 20 days straight) puts it: “now is the time I work to wear myself out, I’ll keep going for as long as my body can take it". Sadly, death’s presence goes way beyond the metaphor. Fear of violence is a strong component of their shared experience as they find themselves vulnerable to robberies, kidnapping and murders. It is not uncommon to read news stories about an Uber driver's body being found after he or she was reported as missing.

Thus, while Uber's business model and technological development revolves around mitigating uncertainty through data processing and predictive modelling, it turns out drivers are all too used to managing uncertainty at their own expense. The difference lies in scale. Uber wants to stabilize the “real world”, predict demand, manage labor and rationalize cities' dynamics across the globe. For drivers, uncertainty hits much closer: it is about whether they will make it through the month, or even to next day. It is about feelings of fear, despair, hope, resilience, pride and tiredness.

Drivers are well aware of how precarity constitutes their daily routines, and fight to make a difference. Better fares and more safety have been their main demands for a while. For now, they spot no signs of better working conditions once things go back to "normal". Some argue the pandemic is actually the right time for drivers to get their voices heard — if only people would stop "risking their lives for handouts", laments a driver in Samuel's post. As income uncertainty keeps rising, however, a sense of practical urgency seems to prevail. I ask Giacomo what drivers’ major needs are at this time. He promptly tells me: "what we need is rides. We need rides".

Notes

-

Uber’s rhetoric often appeals to the management of “the real world”. This is observable in publications on Uber’s Engineering blog, patent applications and prospectus. ↩

-

Rosenblat and Stark (2016) refer to this as “algorithmic labor”. ↩

-

This number includes both Uber drivers and UberEats couriers. Although the second group is also deeply affected by the pandemic, this article focuses on the first one. Their classification as “partners” are part of Uber’s rhetoric, which avoids recognizing them as workers, let alone proper employees. ↩

-

Deadline later updated to June 8th. ↩

-

The Federal Government launched a BRL 600,00 (approximately USD 105,00) to which certain groups, among which informal workers, may apply. ↩

References:

Butler, J. Human Traces on the Surfaces on the World. Contactos https://contactos.tome.press/human-traces-on-the-surfaces-of-the-world/

Mackenzie, A. (2015): The Production of Prediction: What does machine learning want? European Journal of Cultural Studies, 18(4-5), 429–445. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367549415577384

Rosenblat, A., Stark L. (2016) Algorithmic Labor and Information Asymmetries: A Case Study of Uber’s Drivers. International Journal Of Communication, 10, 3758–84. http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2686227